According to the prompt-copy in front of him, it is the opening of Act IV, and the drunken military doctor, Chebutykin, should be promising to turn over yet another new leaf, while Irina, the youngest and flightiest of the sisters, steels herself for marriage to the honourable but dull Baron Tuzenbakh.

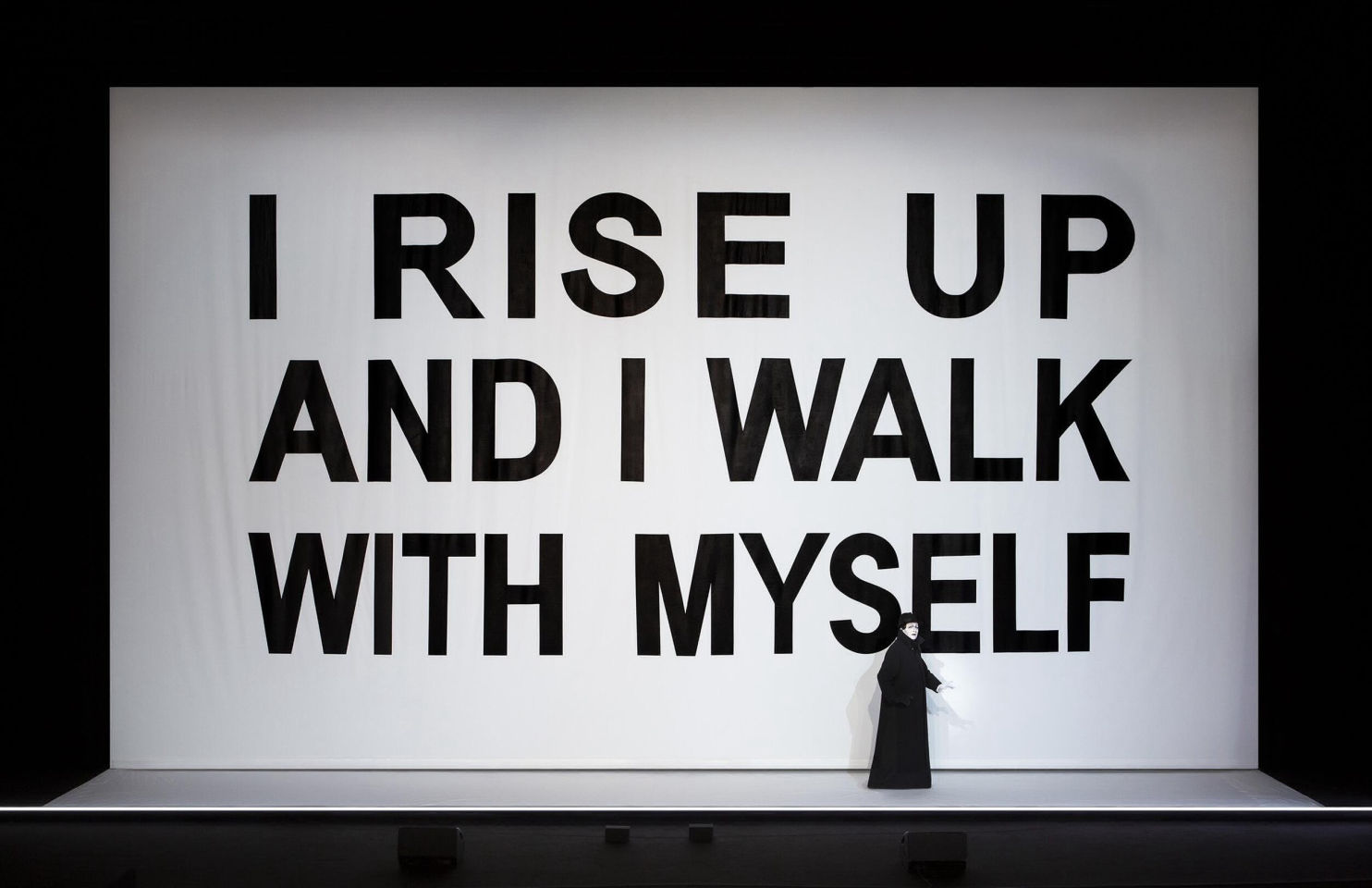

However, nothing on stage seems remotely to suggest this. Wilson is still working on what he terms "the visual book", and Chekhov's dialogue has been largely shorn away. In an entirely invented prologue, the sisters line up for a ghostly identification parade, their faces in a queasy rictus, while an ambling figure - apparently Masha's lover Vershinin - delivers a speech looted from the previous act to a thumping Hip-hop beat.

The scene then dissolves into a completely silent symphony of abstract movement as the doctor bounds around holding a single feather in his hand. Every so often, Wilson rises and moves stealthily into the space to improvise amendments to the choreography, his sinuous 6' 3" frame shuddering as if possessed by some avant-garde demon. At other times, he simply directs the actors from his chair as if they were puppets, booming at them through a microphone.

Finally, toward the middle of the act, comes the most wayward, incongruous (and ultimately hilarious) of Wilson's visual additions. In the original, the sisters' henpecked brother Andrei is portrayed as a browbeaten figure, always seen wheeling a pram. But here he becomes a crazed automaton, first seen creeping along the upstage wall, and then gathering momentum at an alarming rate. In a climax that is a cross between Bauhaus and Keystone Kops, the pram ricochets around the space like apinball, bouncing comically off the huge cylinders that Wilson has substituted for fir trees.

"I tell the actors, 'Forget Chekhov'," says Wilson in a break, "'Don't think about Chekhov. It'll be a mess if you do. Nobody can even imagine how some of the things are going to relate when we put back the text. Of course I know the story, but I try to forget it myself. That way I can look at the gestures just as gestures and the movement as movement. It gives me a kind of freedom."

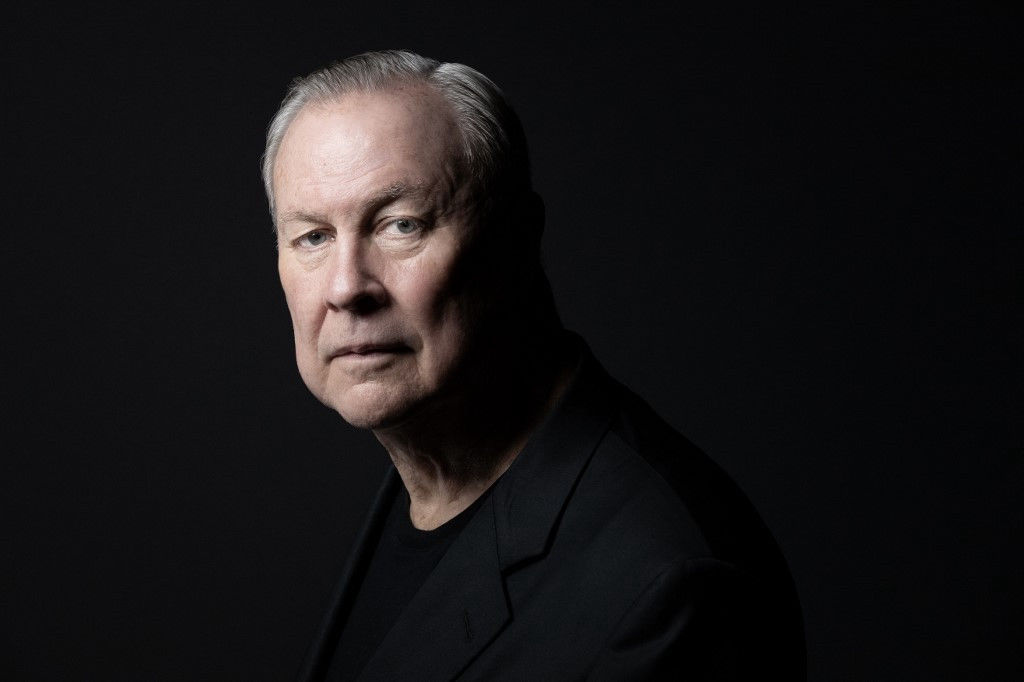

Dismissed as a charlatan by his detractors and exalted as a visionary by his fans, Robert Wilson is one of the world's most innovative theatre directors, a mercurial force who ranks in the 20th-century experimental pantheon alongside such giants as Meyerhold, Grotowsky, Brook and Pina Bausch. His genius for image has shaped theatre over the past 30 years, and remains the most sustained and spectacular argument against the word-bound tyranny of naturalism. Wilson has created not only a style of theatre, but an entirely new dramatic vocabulary. Mel Gussow of the New York Times, says, "Transcending theatrical convention, he draws in other performance and graphic arts, which coalesce into a tapestry of images and sounds."

Primarily a painter who works in theatre, Wilson made his first impression with vast devised works such as the seven-hour Deafman Glance, the seven-day play KA MOUNTAIN AND GUARDenia TERRACE, which took place on a Persian mountainside, and Einstein On The Beach, one of the landmarks of modern music theatre. Often silent, or lacking narrative, or both, these meandering works forced audiences to view theatre in a different way. "Go as you would to a museum, as you would look at a painting," Wilson said. "Appreciate the colour of the apple, the line of the dress, the glow of the light. You don't have to listen to the words, because the words don't mean anything. You just enjoy the scenery, the architectural arrangements, the music, the feelings they all evoke. Listen to the pictures."

Widely lauded as the successor to the surrealists, he has produced some of modern theatre's most defining images: the two uneasy Victorians in Einstein, who, incarcerated in a carriage, slide along to the sound of Philip Glass's arpeggios; or the floating incandescent Grail of Parsifal: "I never saw anything more beautiful in the world since I was born," wrote Louis Aragon in an "open letter" to fellow Surrealist writer André Breton, after seeing Deafman Glance in 1970. "It is what we, who fathered surrealism, dreamed might come after us, beyond us."

The 80s and 90s saw Wilson shift towards more conventional theatre, and to opera, but he retained the same entirely visual approach. Classic texts by Ibsen, Euripides and Shakespeare are treated as just another element, a kind of verbal music. Sometimes this has proved successful: "A Dream Play has never succeeded in the theatre, to my knowledge, until Robert Wilson decided to stage it," wrote the critic Robert Brustein of the Strindberg production that premieres at the Barbican on May 29. "Wilson solves its insoluble problems largely by ignoring them completely."

At other times, critics, particularly in England, have been less than enamoured of Wilson's approach. But even in his less successful work, he still manages to produce some of the world's most arresting, crusading, and wildly beautiful theatre: "I can't think of any body of work as large or as influential," says Susan Sontag. "To be so prolific, to have such a large palette, to do so many different things is part of his genius. His is the great theatre career of our time."

In person, Wilson is the consummate showman of the bizarre. An imposing 59-year-old Texan with a syrupy, monotonous drawl, he is both mesmerising and intimidating. He always dresses in the same way - dark jacket and dark polo-neck. Even his face has a strange, powerful symmetry. "He's like someone who worked for the space programme, like a scientist or a doctor," says Tom Waits, who worked with Wilson on The Black Rider and Woyzeck. "Definitely someone who knew a whole lot about something. Of course, Bob is also a Texan, a lover of tall tales and a great storyteller."

Much of the folklore surrounding Wilson has the flavour of legend: he thinks, apparently, only in pictures, has read few books (seven is the number sometimes quoted), and, some confidants claim, can only eat food served in certain geometric proportions. Most intriguing and troubling is his guru-like status in the 70s among a group of like-minded disciples known as the Byrds, and his collaboration with disabled or mentally disturbed children. Certainly, Wilson is particularly adept at mythologising his own life, with stories of nervous conditions, stutters and mysterious cures that even his own sister cannot recall: "I've read articles and thought: 'Oh god did we grow up in the same house?'" says Suzanne Wilson, "He does create a kind of mystique about his life."

However, some of the stories of Wilson's obsessions and iron-clad whims are just plain weird. In 1980, while devising a show called Edison, Wilson defied scepticism to persuade a German factory to produce a gigantic light-bulb: "Every time we flew anywhere," recalls sound designer Hans Peter Kuhn, "The light-bulb had its own seat."

Wilson can often be quite warm and is a great raconteur: "Sometimes it seems that he's on another planet," says the musician David Byrne, who worked with him on the CIVIL warS and the Forest, "And sometimes you can go out drinking with him after rehearsals and just have the biggest giggle in the world." On other occasions, though, his temper can be quite merciless: "Bob could totally charm you one minute and totally terrorise you the next," says Charles Dennis, who worked with him in the early 70s, "he could all of a sudden have this temper fit and scare the shit out of you. It was like a thunderstorm you never saw coming."

It is this manic drive that propels Wilson. He takes no holidays, and spends every waking moment at work: rehearsing or jetting between venues by day, and making drawings for new productions by night. "The musician and performance artist Laurie Anderson recalls Wilson in Paris, juggling two productions. "To get him from one theatre to the other he hired an ambulance, which also allowed him to sleep in the back. Flying through Paris in the back of an ambulance. For me, that image pretty much sums Bob up."

He still keeps his Spring Street loft in New York, but only spends about 10 days there each year. He earns vast sums for his productions, but lives modestly and ploughs his fees back into the non-profit organisation that supports his work, the Byrd Hoffman Foundation. His close personal relationships, centred in the 70s around his troupe and in particular his then long-term partner, the dancer Andy de Groat, is now scattered over continents, with boyfriends at various ports of call. "There are partners," he says, in a typically Wilsonian comment on his personal life, "I don't see so much difference. Now I'll go home and watch television. Now I have sex. Now I'm with my boyfriend. Now I go to work. I don't see it as separate."

Robert Mims Wilson was born in the Southern Baptist stronghold of Waco, Texas on October 4 1941, the first child of Loree (nee Hamilton) and DM Wilson, a real-estate lawyer. For the most part, the family regime was punctilious: "My mother was rather severe, very formal, cool in her nature," he says, "very modest in her dress. I was never touched that I can remember as a child; the first time I can remember her kissing me was when I went away to the University of Texas."

As a consequence, the young boy would withdraw into himself: "I was pretty much a loner growing up. I would come up from school and go into my room and close the door and could entertain myself." However, even at this young age, Wilson had some of the magnetism that would later become such an asset. "He was sort of like a pied piper," says his younger sister Suzanne. "He was always very tall and very handsome and he just had a certain charm. He had that ability to get people to follow him and do things; he was always organising plays and clubs." He also nurtured an early ambition to be a painter.

At 17, Wilson was taken to an eccentric local dance instructor called Bird "Baby" Hoffman, apparently in the hopes of curing a stutter: "She just said 'take more time'. And I begaaaaaann tooooooo taaaaallllk like that," he says. "It was amazing. In a couple of months I had almost overcome this thing." The encounter with Hoffman, with her dyed red hair and immaculate white dresses, was to be the first of those, mythical, pivotal events that mark out Wilson's creative trajectory. She would become the inspiration for many of his early works and give a name to his first communal troupe; he even for a time began calling himself Byrd Hoffman: "She was probably the first artist I ever met," he says.

After school, mostly to please his father, Wilson enrolled on a business administration course at the University of Texas, but dropped out in 1962 to study interior design at the Pratt Institute in New York. Here, he encountered mainstream theatre for the first time: "I went to see the Broadway plays. I hated them and I still do, for the most part. I then went to the opera and I didn't like that either." But then he saw the work of the choreographer George Balanchine and liked that "a lot, because of the mental space, because of the virtual space". He also saw the work of choreographer Merce Cunningham and his musical collaborator John Cage, "and that was a confirmation of everything".

However, difficulties assimilating into the new East Coast environment and tensions at home began to put an unbearable strain on Wilson. In 1964, during rehearsals for one of his first plays, he suffered a mental breakdown: "I wanted to kill myself. I spent six weeks in an institution. It was quite terrifying, six weeks locked up in Texas."

After being released, Wilson returned to New York, and on graduation, began to immerse himself in the New York art scene, working with the Choreographer Alwin Nikolais and designing the Motel Section of Jean-Claude van Itallie's landmark piece America Hurrah. He also continued the therapeutic work with mentally and physically disturbed children and adults that he had begun at university as a student job to make ends meet. At a New York hospital he directed a "ballet" for iron-lung patients, where the "dancers" moved a fluorescent streamer with their mouths while the janitor danced dressed as Miss America.

The most significant development of this period was the foundation of the Byrd Hoffman School of Byrds. This was a group of mostly non-actors Wilson discovered on the street, at workshops, even in burger joints. In a more temperate version of Warhol's Factory, they met regularly at Wilson's Spring Street loft (which became known as the Byrd Loft), had regular communal meals and gathered every Thursday for "open house" sessions of dancing and smoking marijuana.

Among the earliest of the Byrds was dancer Andy de Groat, Wilson's partner right up to the time of Einstein On The Beach: "The personal aspect was completely integrated in the work that we were doing," says de Groat, who now works as a choreographer in Paris. "We were rehearsing and living in the office, it was everything and everyone at the same time, the kind of craziness that you can deal with when you are 20 years old. It was exhausting. Bob can be very demanding, very precise, the kind of intensity that people can support only for a certain amount of time."

However, the Byrd Hoffman School acted primarily as an incubator for Wilson's early pieces: "We felt we were working as much on the self as on the work," says Sheryl Sutton, one of the early members. "It was like a laboratory. We were doing research on perception and communication. And each of us had a forte, something we would do especially well, and incorporate it into the play."

Wilson's first major work with the Byrds was The King Of Spain, in 1969. Enormously influenced by the work of Cage and Cunningham, it featured many aspects that still survive. Wilson directed almost entirely visually, intuitively, communicating mostly through drawings: "Whenever he had to make an announcement he would whisper it," says Sutton. "He used to wear dark glasses and stare at the floor and fidget with a pencil. He'd never look at anybody. There was no verbal communication." The resulting work was a silent, glacially progressing piece, in a 19th-century picture-frame style, that featured such striking images as a set of giant furry legs slowly traversing the space, as if an enormous cat were walking through, and the outsize head of the King of Spain, turned away from the audience until the final moments.

Later that year, Wilson expanded the piece into what became The Life And Times Of Sigmund Freud, a four-hour work which incorporated The King Of Spain as its second act, adding an opening scene on a beach, in which the performers perform simple everyday actions, spin and dance. In the final act, a group of exotic wild animals enter a painted 2-D cave as naked boys and girls play languorously in the distance. Richard Foreman wrote in the Village Voice, "In this new Aquarian age, or in whatever new era we're coming upon, this is the kind of theatre we need."

However, Wilson's next piece, 1970's Deafman Glance, would make an international impact. The inspiration was a 12-year-old black deaf-mute boy named Raymond Andrews, whom Wilson met in 1968 in Summit, New Jersey, when he intervened to stop the boy being beaten by a policeman. Wilson later discovered that Raymond lived in a two-room apartment with 12 family members, and, with the agreement of his parents took Raymond to live with him, in the hopes of educating him.

But it was Raymond who ended up educating Wilson: "What interested me about Raymond was that he did not know any words," Wilson says. "His imagination was primarily visual." From observations of Raymond, a palette of movements and ideas was built up which became the raw material for the seven-hour piece. Perhaps the most striking image comes in the 20-minute prologue, in which a black matron in Victorian dress slowly pours a glass of milk before silently stabbing her two children. The back wall splits open to reveal a dreamscape, quietly observed by the deaf boy Raymond, perched high above the stage.

"This miracle has come about, long after I stopped believing in miracles," gushed Aragon after the sensational Paris premiere. Wilson was, at first, unable to appreciate the significance: "I didn't know who Louis Aragon was, I didn't know André Breton. I knew nothing. But my agent did tell me: 'If you want, for the rest of your life you can work in the theatre. You have had a phenomenal success.'"

Wilson was invited to Iran in 1972 to perform in the Shiraz festival, for which he created a seven-day piece entitled KA MOUNTAIN AND GUARDenia TERRACE. However, the project was halted for a month, when he was detained at Athens airport when customs officials discovered a bag of marijuana in his luggage. After Jackie Onassis secured his release, he joined the others in Iran, covering an entire mountain with various tableaux: a cardboard suburbia called "fifty houses", cut-out dinosaurs, a forest of spindly flamingoes. Each day's activities were based on specific colours, seasons and elements.

Returning to New York, Wilson mounted The Life And Times Of Joseph Stalin, a 12-hour compilation of all of the "silent operas" that he had done to that date. However, he was already making preparations for his next major project, A Letter To Queen Victoria, which would introduce a Wilsonian bombshell: language. This bold initiative was precipitated by Wilson's encounter with his second child "muse", a 14-year-old autistic boy named Christopher Knowles, entrusted to Wilson by his liberal-minded parents. He lived in the loft for about three or four months, working with the group and enjoying it. Christopher's father, Ed Knowles has said, "He had his reservations at first but eventually he really got into the work, and became part of the scene."

Wilson had long acknowledged a certain element of autism in his own personality, a trait that is certainly evident in much of the work, in the obsessive use of patterns and counting. As he had done with Raymond Andrews, Wilson made Christopher the engine for the new piece, studding the text with his fragmented, disjointed poetry: "Emily, Em, Em, Em, Emily likes the TV. Because she watches it. Because she likes it. Em, Em, Em, Emily likes the TV," went one repetitive mantra. Wilson even went as far as teaching the cast Knowles' manner of speaking

However, Letter To Queen Victoria signalled the dissolution of the Byrds; for the first time they were required to audition and would soon be phased out altogether as Wilson moved towards professional actors. Some of the Byrds, however, saw their lives transformed by their involvement with Wilson, going on to become lighting designers, performers, or in the case of Christopher Knowles, an artist with work hanging in some of the world's best known galleries.

Many had considered the group a family and were bitterly disappointed: " People made a mistake with that kind of man," says ex-Byrd Ann Wilson, "They thought he was their friend."

But the production that would mark Wilson's drive away from the lofts of SoHo and towards the cool, clean minimalist lines now so prominent in his work, was Einstein On The Beach, his collaboration with the composer Philip Glass. The two met backstage at Letter To Queen Victoria and decided to make a piece together: "We got together once a week," remembers Glass, "in this little restaurant where Bob would draw, and over about six or eight months that book of drawings became the basis of Einstein."

The resulting four-and-a-half-hour work, developed over a year of rehearsals, was a spectacular collage of images: a huge smoke-belching cardboard locomotive; a massive bed in the middle of a courtroom. At one point, Wilson himself performed a frenetic, jolting "torch" dance, holding a pair of flashlights. However, most impressive was the closing tableau: a giant spaceship flashing esoteric symbols in time to Glass's soaring repetitions.

The French first lauded Einstein, with a rapturous reception at the Avignon festival in 1976. Officials from New York's Metropolitan opera broached the possibility of an American Met premiere: "We were really artists who had come from downtown," remembers Glass. "We thought there wasn't a snowball's chance of it going to the Met." But, the opera played two consecutive Sunday nights there in 1976, to an overwhelming critical reaction: "With this work, [Wilson] is launching theatre into the unknown and the unknowable," Robert Brustein wrote in the New York Times, "[it] makes our contemporary domestic plays look like ancient artefacts of a forgotten age." However, by the end, few of the collaborators were talking to each other, and Wilson and Glass had racked up a combined personal debt of $150,000. The day after the Met premiere, Glass went back to driving a New York taxi.

After Einstein, Wilson was invited to the Berlin Schaubuhne, where, in 1979, he incorporated the character of the Nazi Rudolf Hess into a piece called Death, Destruction And Detroit (one of his text collaborators, Maita Di Niscemi, notes, "It had little to do with Death, and nothing at all with Destruction or Detroit.") Later that year, he would return to Germany for another piece, this time based on Edison.

However, about this time, an idea was brewing in Wilson's mind for one of the biggest theatre projects ever attempted: the CIVIL warS. "After Death, Destruction And Detroit he was wondering what to do," says di Niscemi, "so, I jokingly suggested that he do a history of the world. And he said, 'That isn't a bad idea'."

Wilson's original plan was to assemble the piece in various cities - Rotterdam, Cologne, Tokyo, Marseille, Rome and Minneapolis - with the whole 12-hour piece being assembled for the 1984 LA Olympics. The Rome section, for which Glass composed an underwater opera, was particularly striking, showing Confederate General Robert E Lee in a submarine while glass coffins floated by outside.

However, from the beginning, Wilson faced funding difficulties. Though many of the sections were produced in their respective countries, it was $1.2m short of its funding target, and the whole piece never made it to LA: "It is the only time in my life that I didn't succeed," a tearful Wilson told a BBC documentary in 1984. "Maybe it's being older. I'm getting tired." Wilson was saddled with enormous debt from the project, which would take more than a decade to pay off.

The failure of the CIVIL warS had a profound effect on Wilson's career and would mark the end of such large-scale devised projects. For his first attempts at existing works he made the unlikely choice of Euripides' Alcestis before moving on to Heiner Muller's plays Hamletmachine and Quartet. Since then, Wilson has directed over 50 shows, including King Lear, Hamlet, Ibsen's When We Dead Awaken and The Lady From The Sea, and operas such as Madame Butterfly and The Magic Flute.

Many mourn the abandonment of the imagistic monumentalism of his early pieces, and accuse him of doing too much, too quickly. At the same time, Wilson's later period has produced a few indisputable masterpieces: his hypnotic Parsifal, with its flying-saucer grail, was perhaps the most complete solution to the opera since Wieland Wagner; while The Black Rider, a collaboration with Tom Waits and William Burroughs, was simply an unforgettable orgy of playful, imagistic fun.

And with his latest "grand projet", a $7m temple to theatre on Long Island called the Watermill Center, and numerous forthcoming intercontinental productions, Wilson relentlessly moves forward. "A few days ago I had dinner with a friend of mine," he says, "and he was saying 'Why are you doing this? Go and have a house in the country. Retire, for God's sake!' But there is no way. I don't see very much difference between living and working. I don't see much difference between being in this room or being on stage. The same concern with the way food is placed on the table or how you live or whatever. It's an aesthetic you live with whether you are private or public. It's all a part of one thing."

Born: October 4, 1941, Waco, Texas.

Education: Waco High School (1954-59); University of Texas ('59-62); Pratt Institute, Brooklyn ('62-64).

Works include: The King Of Spain (1969), The Life And Times Of Sigmund Freud ('69) Deafman Glance, KA MOUNTAIN AND GUARDenia TERRACE ('72), The Life And Times Of Joseph Stalin ('73), A Letter For Queen Victoria ('74-5) Einstein On The Beach ('76), Death Destruction & Detroit ('80), the CIVIL warS: a tree is best measured when it is down ('83-4), King Lear ('85), Alcestis ('86), Hamletmachine ('86), Quartet ('88), The Forest ('88), The Black Rider ('90), Parsifal ('91), Dr. Faustus Lights The Lights (92), Madame Butterfly ('93), The Magic Flute ('95), Monsters of Grace ('98), Dream Play (98), Woyzeck (2000), POEtry ('00), Three Sisters ('01).

Awards: Pulitzer drama prize for the CIVIL warS ('86).